Crime detectives search for motives; smart businesses do the same with customers. David Duncan applies this detective mindset to coffee shop in ‘The Secret Lives of Customers.’ He transforms business theory into a mystery where we discover why customers actually buy coffee.

As builders, we obsess over our products while customers live in a different reality. We focus on features and competitors but misunderstand why people buy anything.

Duncan puts it simply: “Products can’t make you do anything. They are a means to an end.”

We act like detectives who measure fingerprints without asking why the crime happened. The shift from product-focus to jobs-focus transforms your development process—instead of adding features customers might want, you solve problems they have.

What job is your customer hiring your product to do? Answer that and you’re halfway to building something essential.

From features to jobs

The usual product development approach is backwards. We ask customers about features, analyze usage data, or copy competitors. This misses the bigger picture.

Two key insights matter:

-

Your product is a supporting actor, not the star

Users don’t care about your dashboard. They want to feel productive, connected, or informed. Your product is just one option.

Figma succeeds not as a better design tool but because it solves collaboration problems other tools couldn’t.

-

Your competitors aren’t who you think they are

Your competition includes anything that solves the same job. That spreadsheet your customers use instead of your platform? That’s your competitor.

Now that we understand our product is one solution to our customer’s problems, we need to figure out what those problems are. This is where Duncan’s research approach becomes essential.

Small data, Big insights

While everyone chases big data, Duncan values “small data” from direct customer conversations.

“Insights from data are only as good as the questions asked.” Analytics matter less than understanding why customers behave as they do.

Duncan offers “The Investigation Method”:

- Imagine: Form initial hypotheses about what jobs your customers might be trying to accomplish

- Investigate: Talk to customers and observe them in their natural environment

- Interpret: Analyze findings and refine understanding of their true motivations

The key interview questions focus on users’ lives:

- What are they trying to accomplish?

- Why do they choose certain solutions?

- Where do they struggle?

Once we’ve gathered these insights from customers, we’ll need a framework to organize what we’ve learned. This is where the job spec comes in.

The Job spec

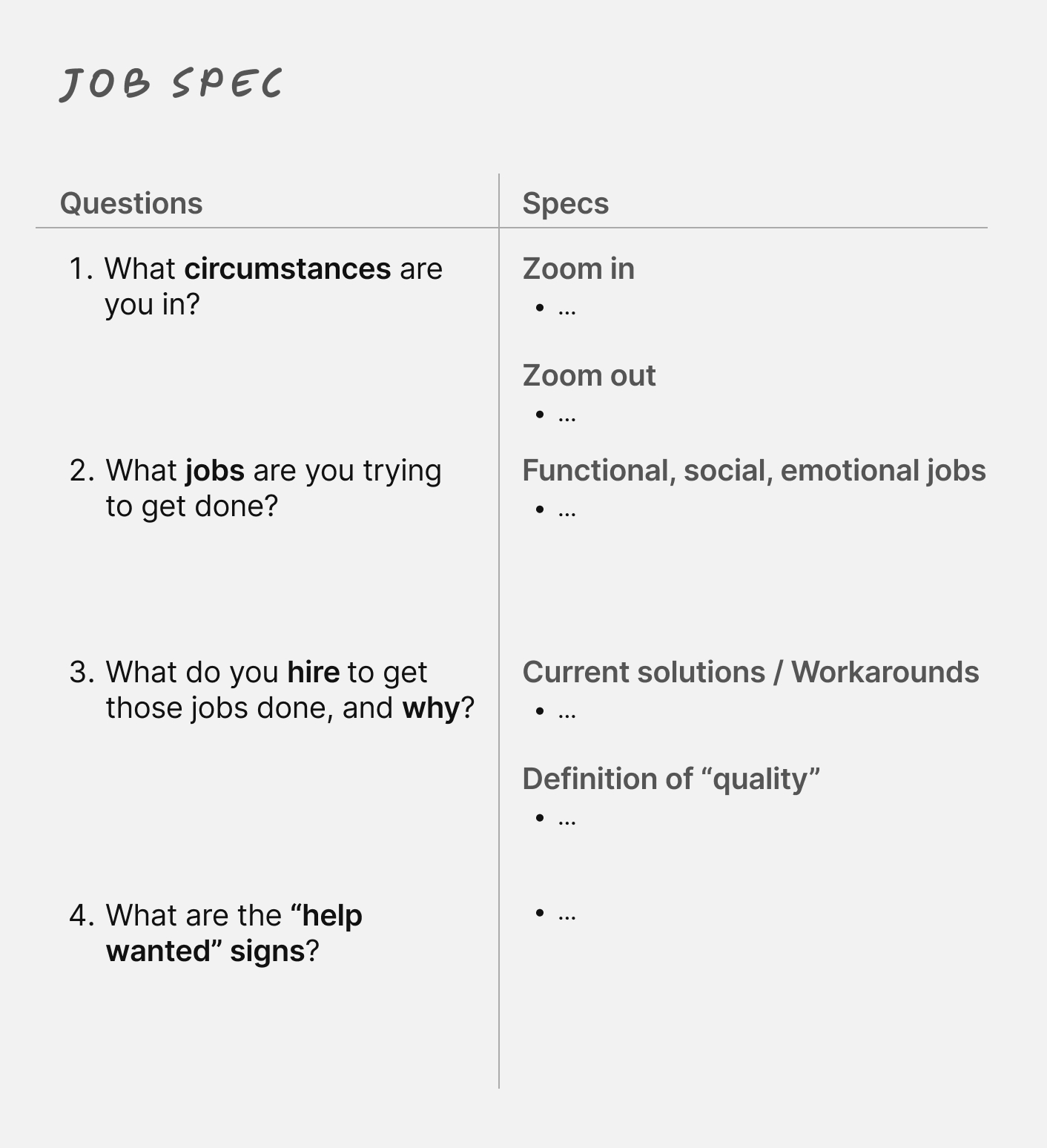

After each customer interview, create a “job spec” to understand needs:

- Circumstances: When and where do needs arise?

- Jobs: What problems need solving? These can be:

- Functional (practical goals)

- Emotional (desired feelings)

- Social (how they want to be perceived)

- Current solutions: What they use now?

- Help wanted signs: Where current solutions fail?

For B2B products, recognize you’re selling to multiple stakeholders. Distinguish between role-based jobs (position needs) and personal jobs (individual needs).

With individual job specs in hand, we’re ready to see the bigger picture by mapping these insights across the entire market.

Mapping the Opportunity space

When you use Duncan’s “Market Map,” you’ll plot what your customers need against when and where they need it.

Each intersection represents a specific situation where a customer needs something solved. Mark which intersections are poorly served to find opportunities.

This approach reveals the full spectrum of customer needs across contexts, helping you spot gaps competitors miss.

What this means for us

If you build products:

- Define quality from the customer’s view. Engineering brilliance means nothing if it solves the wrong job.

- You might serve multiple purposes. Different customers may hire your product for different jobs.

- Measure jobs fulfilled, not just usage. High engagement might signal your product makes a job harder, not easier.

- Look for “help wanted signs”. The biggest opportunities exist where important jobs remain unsatisfied.

- Target specific needs. Products that try to please everyone often please no one.

- Study anomalies. When customers ignore your “brilliant” features, rethink your understanding of their needs.

The Invisible product

Here’s perhaps the deepest insight: users don’t want to use your product. They want to make progress in their lives.

The more invisible your product becomes while serving that progress, the more essential it becomes. The best interfaces feel barely there.

Great products come from understanding the jobs users need done and creating solutions that fulfill those jobs better than any alternative—even when that alternative looks nothing like your product.

In a world obsessed with features, companies that focus on customers’ jobs win.